Should a democratic government be for sale to the best fund-raiser?

-

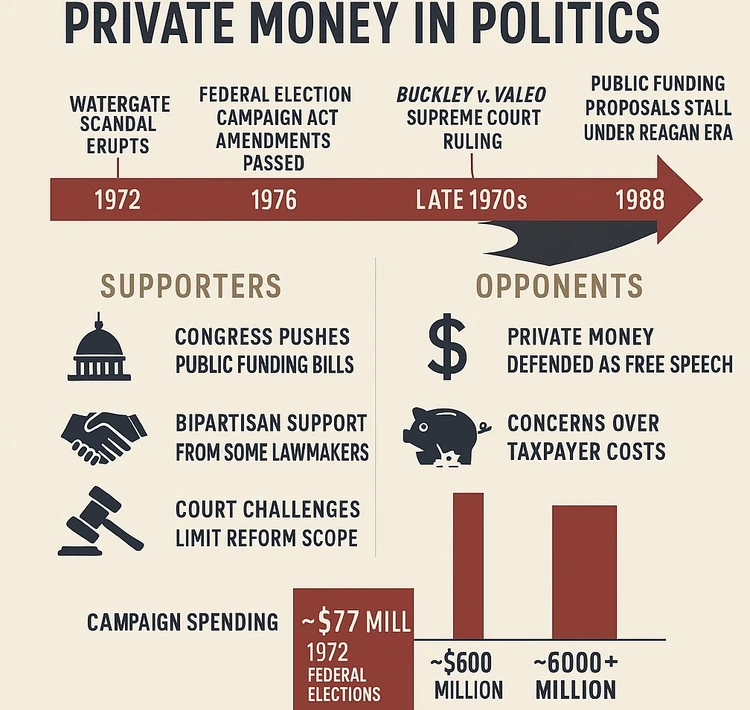

Watergate Fallout: Scandal in the 1970s ignited demands to ban private donations and protect democracy from secret money and corruption.

-

Bold Proposals Stall: Reformers in Congress pushed to replace private cash with public fundsbut legal hurdles and partisan divides blocked sweeping change.

-

Legacy Endures: Though efforts failed, the fight shaped debates still raging today over big moneys grip on U.S. elections.

Money pours into political campaigns today millions of dollars from individual supporters, giant corporations and anonymous donors who back PACs and other private funding efforts.

The Trump campaign raised at least $1.45 billion while the Biden campaign raised about $997 million. After Biden dropped out, the Kamala Harris campaign raised more than $1 billion in just three months.

The net effect is that the American government appears to be and in many ways isfor sale. While money alone can't guarantee campaign wins, a large campaign fund can outweighjust about everything but incumbency in shaping the outcome of an election and, therefore, public policies.

Those who weren't around to see it may not realize that nearly half a century ago, lawmakers and activists fought fiercely to eliminate private financing of elections altogether. During the 1970s and 1980s, a significant wave of reformers believed that only a fully public system could protect democracy from the corrosive influence of big donors and special interests.

John W. Gardner, a Republican who served in Democrat Lyndon Johnson's administration, was the founder in 1970 of Common Cause, a "people's lobby" that pushed strongly for public funding. It still exists but has shifted its priorities other issues.

Gardner and other public funding advocates failed buttheir proposals laid the groundwork for debates that still rage today.

Watergate sparks a reform movement

The modern push to end private funding of campaigns gained momentum after the Watergate scandal, which exposed how President Richard Nixons reelection committee had secretly raised millions from corporate executives, lobbyists, and wealthy individuals. Revelations about secret slush funds and illegal contributions shocked the public and drove Congress to enact the landmark Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA) amendments of 1974.

The FECA reforms imposed new limits on contributions and spending and created the system of public financing for presidential campaigns. But many reformers saw those measures as only partial fixes. They argued that as long as private money remained in the system, politicians would still be beholden to deep-pocketed interests.

Proposals for full public funding

In the years following Watergate, several bills were introduced in Congress aiming to replace private contributions entirely with public funds. One of the most prominent was sponsored by Sen. William Proxmire (D-WI) and Rep. John B. Anderson (R-IL) in the late 1970s. Their legislation would have banned all private donations for federal campaigns and instead allocated taxpayer money to candidates who met qualifying thresholds.

Supporters claimed the system would level the playing field and reduce the appearance or reality of corruption. The only way to restore public confidence in government is to sever the link between money and political favors, Proxmire said on the Senate floor in 1977.

But critics argued that forcing taxpayers to fund politicians they might oppose infringed on individual rights. Some worried that a public funding system could favor incumbents or create cumbersome government oversight over political speech.

Court decisions,political roadblocks

Adding to the challenges, the Supreme Courts 1976 decision in Buckley v. Valeo complicated reformers plans. The Court upheld contribution limits but ruled that spending money to influence elections is a form of protected free speech. This legal precedent made it harder for Congress to impose strict bans on political spending or to mandate an exclusive system of public funding.

In the 1980s, attempts to revive comprehensive public financing proposals repeatedly stalled. President Ronald Reagan and many congressional Republicans opposed new federal spending on campaigns and saw public funding as an unnecessary expansion of government. Even some Democrats were reluctant to abandon private donations, particularly as television advertising costs soared.

The powerful broadcasting lobby fiercely resisted public funding and also opposed widening restrictions on television advertising, a major source of funding for local broadcasters during election years.

Lingering influence

Despite repeated defeats, the efforts of the 1970s and 1980s helped shape public awareness about the influence of money in politics. Many proposals from that era such as matching funds, spending caps, and transparency requirements remain features of todays debates over campaign finance reform.

Recent Supreme Court rulings like Citizens United v. FEC (2010) and the rise of super PACs have only reignited concerns that private money dominates American elections. Reform advocates frequently cite the earlier push for a fully publicly funded system as an example of what might have beenand perhaps still could be.

History shows weve been grappling with this problem for decades, said Meredith McGehee, a longtime campaign finance reform advocate. The question remains: can we ever fully remove the influence of big money from our democracy?

While the dream of eliminating private funding entirely remains unrealized, the fervor of the 1970s and 1980s efforts endures as a reminder that the battle over money and politics is far from newand far from over.

Posted: 2025-07-04 19:15:51