Kids' toys and safety gear, furniture, and supplements are part of this week's recall roundup

March 13, 2026

ProRider bike helmets may fail in crashes

ProRider is recalling several low-cost bicycle helmets because they fail to meet mandatory safety requirements and may not protect riders in an impact.

- Specific hazard: These helmets can fail impact attenuation and stability requirements, increasing the risk of serious head injury or death in a crash.

- Scope/Stats: About 9,546 helmets sold nationwide in multiple colors (blue, green, red, black, purple) from June 2022 through May 2023.

- Immediate action: Stop using the helmet immediately and request a full refund by following the companys destruction-and-photo instructions.

ProRider, Inc., of Kent, Washington, is recalling ProRider Economy, Bike Helmets with turn ring, Bike Helmets Black Foam, BMX Helmet and Toddler Bike Helmets. The helmets were sold in blue, green, red, black and purple, with the model number, manufacture date (MM/YYYY) and serial number on a label inside the helmet. The recall was issued because the helmets violate the mandatory bicycle helmet standard and may not protect users during a crash.

The hazard

The Consumer Product Safety Commission said the helmets do not comply with impact attenuation, positional stability, labeling and certification requirements. If the helmet does not manage crash forces or stay properly positioned, it can fail to protect the riders head, raising the risk of severe injury or death. No incidents or injuries have been reported.

What to do

Consumers should stop using the recalled helmets immediately and contact ProRider for a full refund. To obtain the refund, consumers should destroy the helmet by cutting the straps and then send a photo of the destroyed helmet to org@prorider.com as instructed by the company.

Company contact

ProRider can be reached at 800-642-3123 from 8 a.m. to 1 p.m. PT Monday through Friday, by email at org@prorider.com, or online at www.prorider.com (click Recall at the top of the page).

Source

Wayfair dresser recall cites tip-over danger

Hong Kong Baojia International is recalling 17 Stories 14-drawer dressers sold on Wayfair because the units can be unstable and tip over if not anchored.

- Specific hazard: Unanchored dressers can tip over, posing tip-over and entrapment hazards that can seriously injure or kill children.

- Scope/Stats: About 3,000 units sold on Wayfair.com from September 2023 through January 2026.

- Immediate action: Stop using the dresser in an unsafe manner and contact the firm for a refund.

Hong Kong Baojia International Limited is recalling 17 Stories Furniture 14-Drawer Dressers sold in black, white and brown. The dressers have a metal frame, a wooden top, and 14 collapsable fabric drawers, and measure about 11.8 inches long by 37.4 inches wide by 52.2 inches tall. The recall cites failure to meet the mandatory clothing storage unit standard required by the STURDY Act.

The hazard

The recalled dressers are considered unstable if they are not anchored to the wall, creating tip-over and entrapment hazards, especially for children. Federal regulators said the products violate the mandatory stability standard for clothing storage units under the STURDY Act. No incidents or injuries have been reported.

What to do

Consumers should keep children away from unanchored dressers and stop using the recalled unit in any way that could allow it to tip. Contact Hong Kong Baojia International to request a refund and follow the firms instructions for completing the recall remedy.

Company contact

Consumers can contact Hong Kong Baojia International by email at Baojia_recall@outlook.com.

Source

Playground swing seats can fail and drop kids

LFTE USA is recalling certain commercial playground swing seats because supporting rivets can fail, creating a fall hazard for children.

- Specific hazard: Rivets that support the swing belt seat can fail, causing the seat to break and a child to fall.

- Scope/Stats: About 7,200 swing seats sold nationwide from January 2025 through September 2025.

- Immediate action: Stop using the recalled swings and request a free replacement seat.

LFTE USA Inc. is recalling Playground Swing Set Seats that were sold as part of assembled playground sets. The swing belt seat was sold in multiple colors (black, blue, green, red, tan and yellow) and is marked with code LF-65708 on the seat pad; only swings with model number 999604 are included. The company and regulators say the recall is tied to rivets that can fail and cause children to fall.

The hazard

The rivets used to support the swing seat can fail, which can cause the seat to break during use and create a fall hazard. LFTE USA reported one incident in which a swing broke and a child fell, resulting in a minor injury.

What to do

Consumers should stop using the recalled playground swings immediately and contact LFTE USA to obtain a free replacement swing seat. If the swing is in a public or shared setting, restrict access until the replacement seat is installed.

Company contact

Consumers can contact LFTE USA by email at recall@lfteusa.com.

Source

Kluster magnet game recall warns of ingestion

Stoney Games is recalling Kluster magnet tabletop games because the loose, high-powered magnets are small enough to be swallowed and can cause life-threatening internal injuries.

- Specific hazard: Swallowed high-powered magnets can attract inside the body, causing intestinal perforations, twisting, blockage, blood poisoning and death.

- Scope/Stats: About 151,600 games sold nationwide and online from October 2018 to September 2025.

- Immediate action: Stop using the game, keep magnets away from children, and contact the company for disposal and replacement instructions.

Stoney Games, LLC of Bexley, Ohio, is recalling Kluster Fun Tabletop Magnet Chess Games sold in a black box labeled Kluster. The set includes about 24 magnets, an orange string, an instruction manual and a black storage pouch with Kluster printed on the front; some were also sold in a white pouch with gameplay instructions on the back. The recall was issued because the product violates the mandatory toy standard due to small, loose high-powered magnets.

The hazard

According to the CPSC, the games contain loose magnets that fit within the agencys small parts cylinder, making them a swallowing hazard for children. If more than one high-powered magnet is ingested, the magnets can attract each other (or other metal objects) through intestinal walls, leading to perforations, twisting and/or blockage of the intestines, blood poisoning and death. No incidents or injuries have been reported.

What to do

Consumers should immediately stop using the recalled magnet games and take them away from children. Contact Stoney Games for instructions on how to dispose of the recalled magnets and receive replacement magnets that are not small parts.

Company contact

Stoney Games can be reached at 800-362-0977 from 8 a.m. to p.m. ET, Monday through Friday, by email at klusterrecall@gmail.com, or online at www.klustermagnets.com/recall or www.klustermagnets.com (click Recall at the top of the page).

Source

LIVEHOM fabric dressers recalled for tip-over risk

Simplehome is recalling LIVEHOM 11-drawer dressers sold on Amazon because the units can be unstable if not anchored, creating tip-over and entrapment hazards for children.

- Specific hazard: The dresser can tip if unanchored, posing tip-over and entrapment hazards that can cause severe injury or death.

- Scope/Stats: About 370 units sold on Amazon.com from December 2025 through January 2026.

- Immediate action: Stop using the dresser in a way that could allow tipping and contact Simplehome for a refund.

Shenzhen Lvmukeji Co., Ltd., doing business as Simplehome, of China, is recalling LIVEHOM-branded 11-Drawer Dressers made of fabric. The dressers were sold in black, white, pink, rustic brown and charcoal black and measure about 11.8 inches long, 39 inches wide and 46 inches tall with 11 fabric drawers. The CPSC said the product violates the mandatory clothing storage unit standard required by the STURDY Act.

The hazard

The recalled dressers can be unstable if they are not anchored to the wall, creating tip-over and entrapment hazards that can result in serious injuries or death to children. Regulators said the product fails to meet the mandatory stability standard under the STURDY Act. No incidents or injuries have been reported.

What to do

Consumers should keep children away from unanchored furniture and stop using the recalled dresser in a manner that could allow it to tip. Contact Simplehome to request a refund and follow the companys instructions for completing the remedy.

Company contact

Consumers can contact Simplehome by email at livehomerecall@163.com.

Source

Lidl candy recall flags undeclared hazelnuts

Lidl US is warning customers not to eat Favorina Chocolate Ladybugs German-Style Nougat because the product may contain undeclared hazelnuts, a potentially life-threatening allergen.

- Specific hazard: Undeclared hazelnuts can trigger serious or life-threatening allergic reactions in people with hazelnut allergies.

- Scope/Stats: All lots are affected; UPC 20304492; distributed to Lidl US stores across 10 states and Washington, D.C.

- Immediate action: Do not consume the product; return it to a Lidl store for a full refund.

Lidl US issued an allergy alert for Favorina Chocolate Ladybugs - German-Style Nougat because hazelnuts are not declared on the label. The affected product is identified as all lots with UPC 20304492 and was distributed to Lidl US store locations in Delaware, the District of Columbia, Georgia, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, South Carolina and Virginia. The notice warns that consumers with hazelnut allergies face the risk of severe reactions.

The hazard

Hazelnuts are a known allergen, and the FDA notice warns that people with hazelnut allergies may suffer serious or life-threatening allergic reactions if they eat the affected product. Because the allergen is undeclared, consumers may not realize the risk before consuming it.

What to do

Customers who purchased Favorina Chocolate Ladybugs - German-Style Nougat should not consume the product. Lidl said consumers should return it to their nearest Lidl store for a full refund.

Company contact

Lidl US Customer Care Hotline: (844) 747-5435.

Source

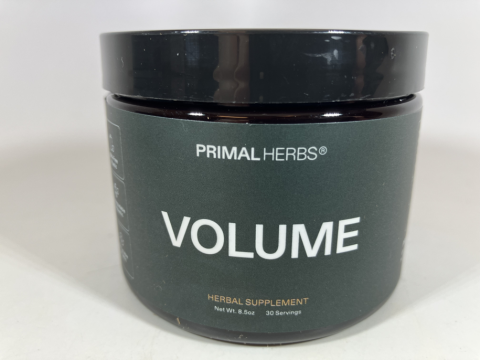

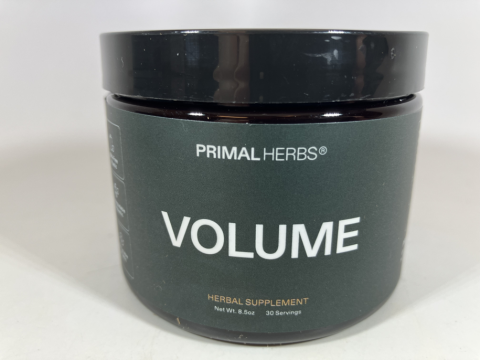

Primal Herbs supplement recall cites hidden sildenafil

Primal Herbs is recalling Primal Herbs Volume after testing found undeclared sildenafil, which can dangerously interact with some prescription medications.

- Specific hazard: Undeclared sildenafil may interact with nitrates (such as nitroglycerin) and lower blood pressure to dangerous levels.

- Scope/Stats: All orders placed between July 2 and September 19, 2025, sold nationwide via primalherbs.com.

- Immediate action: Stop using the product immediately and contact the company for a replacement shipment or full store credit.

Primal Herbs announced a voluntary nationwide recall of Primal Herbs Volume. The company said the product contains sildenafil, an ingredient that was not declared, creating potential risks for consumers taking certain prescription drugs. The recall applies to all orders placed between July 2 and Sept. 19, 2025, purchased through primalherbs.com.

The hazard

According to the FDA notice, sildenafil can interact with nitrates found in some prescription drugs, such as nitroglycerin, and may lower blood pressure to dangerous levels. Consumers with underlying health conditions or those taking medications that can interact with sildenafil may face increased risk if they use the product without knowing it contains the drug.

What to do

Consumers who purchased Primal Herbs Volume during the affected period should discontinue use immediately. Primal Herbs said customers should contact the company to receive a complimentary replacement shipment or a full store credit.

Company contact

Email hello@primalherbs.com or call +1 (856) 420-6117.

Source