Baby and kids clothes are at the top of this week's recall roundup

March 6, 2026

HALO Magic Sleepsuits recalled over zipper

HALO Dream is recalling certain HALO Magic Sleepsuits after reports that a zipper head can detach and create a choking hazard for infants.

- Specific hazard: A zipper head can detach from certain sleepsuits, creating a choking hazard.

- Scope/stats: About 45,000 units sold online at Halosleep.com, Amazon.com, Walmart.com and Target.com (about $50) from September 2025 through February 2026; 15 detachment reports, no injuries reported.

- Immediate action: Stop using the sleepsuit and contact HALO Dream for a refund or replacement.

HALO Dream, Inc., of New York City, is recalling certain HALO Magic Sleepsuit infant sleepsuits because the zipper head can detach. The recalled products have double zippers running down each side of the front and are labeled HALO Magic Sleepsuit. Only specific batch codes are included in the recall.

The hazard

According to the notice, the zipper head can detach from certain sleepsuits, posing a choking hazard to infants. The firm has received 15 reports of the zipper head detaching from the garment; no injuries have been reported.

What to do

Consumers should stop using the recalled sleepsuits immediately. Check the sewn-in label and hang tag for batch codes PO30592, PO30641 and PO30685 (also marked Made in India). Contact HALO Dream to receive a refund or replacement.

Company contact

HALO Dream toll-free at 833-791-0420 (9 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. ET Monday through Friday), email customerservice@sleepsuitrecall.com, or online at www.sleepsuitrecall.com. Consumers can also visit www.halosleep.com and click on Recalls at the bottom of the page.

Source

Forever 21 kids pajama pants fail test

Unique Brands Com is recalling a small number of Forever 21 Kids Disney Mickey Mouse pajama pants because they violate federal flammability standards for childrens sleepwear.

- Specific hazard: The pajama pants violate mandatory flammability standards, posing a burn hazard and a risk of serious injury or death.

- Scope/stats: About 230 units sold on Forever21.com from September 2025 through November 2025 for about $25; no incidents reported.

- Immediate action: Stop using the pajama pants and contact Unique Brands Com to get a full refund with a prepaid return label.

Unique Brands Com, Inc. has recalled Forever 21 Kids Disney Mickey Mouse pajama pants with black stripes after the product was found to violate mandatory flammability standards for childrens sleepwear. The pants were sold in childrens sizes 5/6 through 13/14 and include item number 01334347 on a sewn-in side-seam label below the barcode.

The hazard

The recalled childrens pajama pants do not meet required flammability standards, which increases the risk the sleepwear can ignite and burn quickly. CPSC said this creates a burn hazard and a risk of serious injury or death to children. No incidents or injuries have been reported.

What to do

Consumers should stop using the recalled pajama pants immediately and contact Unique Brands Com for a full refund. The company will provide a prepaid shipping label so consumers can return the pajama pants.

Company contact

Unique Brands Com toll-free at 888-684-5375 (9 a.m. to 3 p.m. ET Tuesday through Thursday), email recall@forever21.com, or online at Forever21.com/pages/product-recalls or Forever21.com (click Recall at the top of the page).

Source

Tomum minoxidil bottles lack child-resistant caps

Belleka is recalling Tomum Minoxidil Hair Growth Treatment spray bottles because they are not child-resistant as required, raising a poisoning risk for young children.

- Specific hazard: The minoxidil-containing serum is packaged in non-child-resistant bottles, creating a poisoning risk if swallowed by children.

- Scope/stats: About 27,400 units sold on Amazon.com from March 2025 through September 2025 for about $20; no incidents reported.

- Immediate action: Secure the product out of childrens reach and contact Belleka for a free replacement with child-resistant bottles.

Belleka Inc., doing business as TOMUM, is recalling spray bottles for Tomum Minoxidil Hair Growth Treatment (100 mL) sold on Amazon because the packaging is not child-resistant. The recalled bottles are silver with a blue wraparound label and a black cap, and they come packaged in a blue box labeled TOMUM and Hair Growth Treatment.

The hazard

The hair serum contains minoxidil, which must be sold in child-resistant packaging under the Poison Prevention Packaging Act. CPSC said the bottles are not child-resistant, creating a risk of serious injury or death from poisoning if the contents are swallowed by young children. No incidents or injuries have been reported.

What to do

Consumers should immediately place the recalled serum bottles out of sight and reach of children. Contact Belleka for a free replacement product that includes two child-resistant bottles of serum (60 mL per unit). Consumers will be asked to dispose of the recalled product bottle and email a photo of the bottle in the trash to tomumcs@gmail.com.

Company contact

Belleka at 862 244-1785 (9 a.m. to 4 p.m. ET Monday through Friday), email tomumcs@gmail.com, or online at https://itomum.com/contact-us/ or https://itomum.com.

Source

Building set recalled over accessible button batteries

RBS Toys is recalling Cubimana Island Storm 3 In 1 Building Sets because children can access button cell batteries in an LED component, creating a potentially deadly ingestion hazard.

- Specific hazard: Button cell batteries in the LED light piece can be easily accessed, creating a serious ingestion hazard.

- Scope/stats: About 3,950 sets sold on Amazon.com from October 2025 through January 2026 for about $30; no incidents reported.

- Immediate action: Take the toy away from children, remove and dispose of batteries, and contact the seller for a refund after disposing of the product.

Shenzhen Ruibosi Technology Co., Ltd., doing business as RBS Toys, is recalling Cubimana Island Storm 3 In 1 Building Sets (model HG1004) sold on Amazon. The 781-piece set comes in a black box with images of a pirate base and pirate ship. CPSC said the toy violates mandatory toy safety requirements because button cell batteries in the LED light piece are accessible.

The hazard

The battery compartment within the LED light piece contains button cell batteries that can be easily accessed by children. If swallowed, button cell or coin batteries can cause severe internal chemical burns, serious injuries, and death. No incidents or injuries have been reported.

What to do

Consumers should immediately take the building sets away from children, stop using the recalled toys, and remove and properly dispose of the batteries. To receive a full refund, consumers will be asked to throw the product away and email a photo of the disposed product to productrecall@cubimanatoys.com.

Company contact

RBS Toys by email at productrecall@cubimanatoys.com.

Source

CPSC flags CCCEI power strips for fire risk

The CPSC is warning consumers to stop using CCCEI power strips sold on Amazon because they lack supplementary overcurrent protection and can pose a serious fire risk if overloaded.

- Specific hazard: The power strips lack supplementary overcurrent protection, increasing the risk of fire if overloaded.

- Scope/stats: CCCEI power strips with 6-foot, 10-foot, or 15-foot cords were distributed via Amazon.com; the notice is a CPSC warning, not a standard recall.

- Immediate action: Stop using the power strips immediately and consult the CPSC notice for safety guidance.

The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission is urging consumers to stop using CCCEI brand power strips immediately due to a fire risk. The power strips have a black metal enclosure with six receptacles and individual on/off switches and were sold with 6-foot, 10-foot, or 15-foot cords.

The hazard

CPSC said the power strips do not contain supplementary overcurrent protection, which creates a risk of fire if the power strips are overloaded. A resulting fire can cause serious injury or death from smoke inhalation and burns.

What to do

Consumers should stop using CCCEI power strips with 6-foot, 10-foot, or 15-foot power cords immediately. If you believe you have experienced a problem related to overheating, melting, or fire, report it to the CPSC and keep the product away from use until you have reviewed the official guidance in the notice.

Company contact

The CPSC notice did not list a company contact for this warning. Consumers should use the source link below for the full CPSC notice and any updates.

Source

Heated insoles warning cites battery fire danger

The CPSC is warning consumers to immediately dispose of Junsyoung heated insoles sold on Amazon because an internal lithium-ion battery can overheat and ignite.

- Specific hazard: The lithium-ion battery can overheat and ignite, creating a fire hazard and risk of serious burns.

- Scope/stats: Junsyoung heated insoles (also associated with seller name JAMRIC on receipts) were sold on Amazon from July 2023 through March 2024.

- Immediate action: Dispose of the heated insoles immediately following local hazardous-waste procedures.

The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission is warning consumers to stop using Junsyoung heated insoles immediately due to a fire hazard. The insoles are black and red, contain a lithium-ion battery in the heel, and are operated by remote control; Junsyoung or seller name JAMRIC may appear on the purchase receipt.

The hazard

CPSC said the internal lithium-ion battery can overheat and ignite while in use. That can lead to a fire and serious burn injuries, particularly because the product is worn close to the body.

What to do

CPSC urges consumers to dispose of the defective heated insoles immediately and follow local hazardous-waste disposal procedures for products containing lithium-ion batteries. Do not continue using, charging, or storing the insoles indoors if you suspect overheating or damage.

Company contact

The CPSC notice did not provide a company contact for this warning. Consumers should review the full CPSC notice at the source link below for additional details and updates.

Source

UHOMEPRO dressers flagged for tip-over hazard

The CPSC is warning consumers to stop using UHOMEPRO 5-drawer dressers because they are unstable when not anchored and violate a mandatory clothing storage standard.

- Specific hazard: The dressers can tip over if not anchored, creating tip-over and entrapment hazards for children.

- Scope/stats: UHOMEPRO 5-drawer dressers (15.7 by 26 by 38.6 inches; about 66 pounds) were sold online at Walmart.com for about $100 and may have been sold elsewhere.

- Immediate action: Stop using the dresser and either anchor it securely to the wall or dispose of it; do not resell or give it away.

The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission is warning consumers to stop using UHOMEPRO 5-Drawer Dressers immediately due to a tip-over and entrapment risk. The dressers are not labeled and were sold in white, black, and brown with five drawers.

The hazard

CPSC said the dressers are unstable if they are not anchored to the wall, which can lead to tip-over and entrapment incidents that cause severe injuries or death to children. The agency said the dressers violate the mandatory standard for clothing storage units required by the STURDY Act.

What to do

CPSC urges consumers to stop using the UHOMEPRO 5-Drawer Dresser immediately. Consumers should either dispose of it in accordance with local disposal requirements or anchor it securely to the wall. Do not sell or give away these hazardous clothing storage units.

Company contact

CPSC asks consumers to report any incidents involving injury or product defect at www.SaferProducts.gov.

Source

Full-face snorkel masks warning cites drowning risk

The CPSC is warning consumers to stop using OUSPT full-face snorkel masks because breathing problems and elevated carbon dioxide levels can lead to loss of consciousness and drowning.

- Specific hazard: The mask can cause labored breathing and increased carbon dioxide, which can lead to loss of consciousness and drowning.

- Scope/stats: OUSPT full-face snorkel masks were sold on Amazon.com from March 2019 through February 2026.

- Immediate action: Stop using the mask immediately and dispose of it; do not resell or give it away.

The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission is warning consumers to stop using OUSPT full-face snorkel masks immediately due to a drowning hazard. The full-face masks have a snorkel tube at the top center and OUSPT printed on the snorkel tube; they were sold in various colors.

The hazard

CPSC said the mask can cause consumers to experience labored breathing that may lead to loss of consciousness or excess fluid in the lungs, increasing drowning risk. The agency also warned the mask can cause increased levels of carbon dioxide, which can worsen breathing difficulty while in the mask.

What to do

CPSC urges consumers to stop using the OUSPT full-face snorkel masks and immediately dispose of them. Do not sell or give away these masks. If you experience breathing difficulties or symptoms after use, seek medical attention.

Company contact

CPSC asks consumers to report any incidents involving injury or product defect at www.SaferProducts.gov.

Source

Flameless candles warning highlights coin battery access

The CPSC is warning consumers to stop using Jolnyus LED flameless candle sets because a coin battery in the remote can be easily accessed by children, creating a potentially fatal ingestion hazard.

- Specific hazard: A lithium coin battery in the remote control can be accessed by children, and required Reeses Law warnings are missing.

- Scope/stats: Two-candle sets (about 6 inches tall) sold on Amazon.com from March 2024 through September 2025 for about $20.

- Immediate action: Stop using the candles and dispose of the set; dispose of or recycle the coin battery following local hazardous-waste guidance.

The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission is warning consumers to stop using Jolnyus LED flameless candle sets immediately due to a coin-battery ingestion hazard. The LED candles were sold in sets of two in ivory, and the packaging is marked volnyus, according to the notice.

The hazard

CPSC said the lithium coin battery in the remote control can be accessed easily by children, creating a serious ingestion hazard. The agency also said the candle sets and remote control do not include required warnings under Reeses Law. Swallowed button cell or coin batteries can cause severe internal chemical burns and death.

What to do

CPSC urges consumers to stop using the LED flameless candle sets immediately and dispose of them. Do not sell or give away these hazardous products. The coin battery in the remote controls should be disposed of or recycled in accordance with local hazardous-waste procedures.

Company contact

CPSC asks consumers to report any incidents involving injury or product defect at www.SaferProducts.gov.

Source

Magnetic stick figure toys pose ingestion hazard

The CPSC is warning consumers to stop using TOP MAGNETS Magnetic Men sets because detachable high-powered magnets can be swallowed and cause severe internal injuries.

- Specific hazard: Detachable magnets are stronger than permitted and small enough to be swallowed, risking intestinal perforation and death.

- Scope/stats: Sets of 12 flexible stick figures sold online at Amazon.com from June 2024 through October 2025 for about $9, and possibly by third-party sellers elsewhere.

- Immediate action: Stop using the toys immediately and dispose of them; do not resell or give them away.

The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission is warning consumers to stop using TOP MAGNETS Magnetic Men stick figure toy sets immediately. The sets include 12 flexible silicone stick figures in various colors, each with four small magnets in the hands and feet.

The hazard

CPSC said the figures arms and legs with magnets can detach when pulled. The toy sets contain stronger-than-permitted magnets that fit within CPSCs small parts cylinder and violate mandatory toy safety standards. If high-powered magnets are swallowed, they can attract inside the body, causing intestinal perforations, twisting, blockage, blood poisoning, and death.

What to do

CPSC urges consumers to stop using the magnetic stick figure toy sets immediately and dispose of them. Do not sell or give away these hazardous magnetic toy sets. If you suspect a magnet has been swallowed, seek emergency medical care immediately.

Company contact

CPSC asks consumers to report any incidents involving injury or product defect at www.SaferProducts.gov.

Source

Miss Vickies chips alert for undeclared milk

Frito-Lay issued a voluntary allergy alert for certain Miss Vickies Spicy Dill Pickle Potato Chips because the product may contain undeclared milk.

- Specific hazard: Undeclared milk allergen can trigger serious or life-threatening allergic reactions in sensitive consumers.

- Scope/stats: Affected product distributed in Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas; identified by UPC 0 28400 761772 and a Guaranteed Fresh date of 21 APR 2026 (manufacturing codes 38U3014144, 8U101514).

- Immediate action: Do not eat the chips if you have a milk allergy; discard the product and contact the company for assistance.

Frito-Lay is alerting consumers to a voluntary allergy issue involving Miss Vickies Spicy Dill Pickle Potato Chips due to undeclared milk. The FDA notice says people with an allergy or severe sensitivity to milk could face a serious or life-threatening reaction if they eat the product.

The hazard

Milk is a major food allergen, and undeclared milk in packaged foods can cause reactions ranging from hives and swelling to anaphylaxis in highly sensitive individuals. The notice specifically warns that those with a milk allergy or severe sensitivity are at risk if they consume the affected chips.

What to do

Consumers with a milk allergy or sensitivity should not consume the product. Discard the chips immediately and contact Frito-Lay through the Miss Vickies Contact Us page or by phone for next steps.

Company contact

Call 1-877-984-2543.

Source

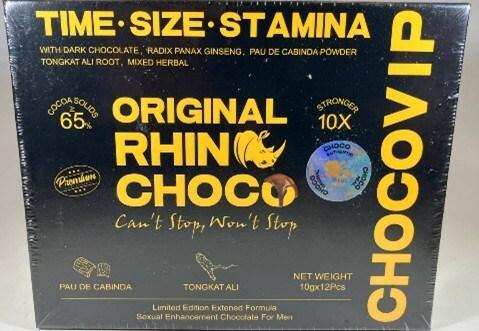

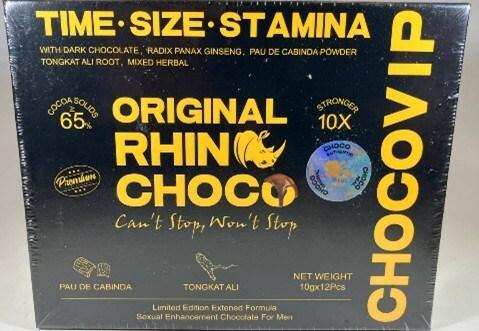

Rhino Choco VIP 10X recalled for drug ingredient

USA LESS Co. is recalling Rhino Choco VIP 10X because it contains undeclared tadalafil, which can dangerously interact with certain prescription medications.

- Specific hazard: Undeclared tadalafil may interact with nitrates (such as nitroglycerin) and lower blood pressure to dangerous levels.

- Scope/stats: Product sold in retail stores and through online sites; identified by UPC 724087947668 and expiration date 10/2027.

- Immediate action: Stop using the product and return it to the place of purchase for a full refund.

USA LESS Co. is recalling Rhino Choco VIP 10X after testing found an undeclared drug ingredient, tadalafil. The FDA warning notes the ingredient can create serious health risks, especially for consumers taking nitrate medications often prescribed for heart-related conditions.

The hazard

Tadalafil can interact with nitrates found in some prescription drugs, including nitroglycerin, and may cause a dangerous drop in blood pressure. The FDA also notes that people with diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, or heart disease often take nitrates, which increases the risk of a harmful interaction if they use the recalled product.

What to do

Consumers should stop using Rhino Choco VIP 10X. Those who purchased the product from usaless.com are urged to return it to the place of purchase for a full refund. If you have health concerns or think you experienced an adverse reaction, contact a health care provider.

Company contact

Call 1-800-872-5377 or email 409749@email4pr.com.

Source

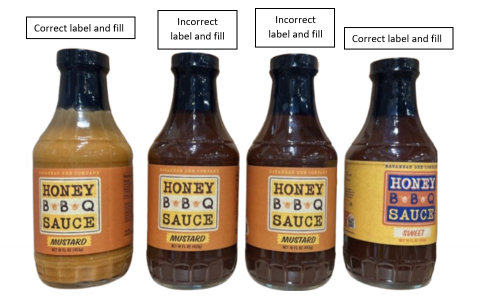

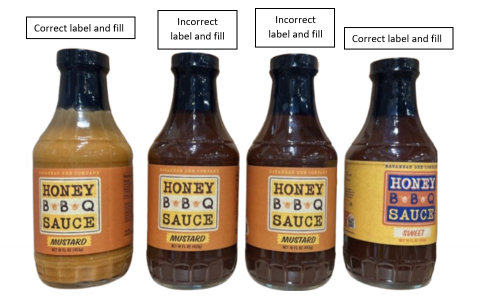

Savannah Bee sauce recalled for undeclared allergens

Savannah Bee Company is recalling Honey BBQ Sauce-Mustard because it may contain undeclared wheat and soy, posing a serious allergy risk.

- Specific hazard: Undeclared wheat and soy can trigger serious or life-threatening allergic reactions.

- Scope/stats: Distributed nationwide to distribution centers, retail stores, and consumers; identified by batch code B1L1360525, Best Before 05/16/27, UPC 8 50033 93758 9.

- Immediate action: Do not consume the product if you have wheat or soy allergies; dispose of it and request a refund.

Savannah Bee Company is recalling its Honey BBQ Sauce-Mustard because the product contains undeclared wheat and soy. The FDA notice warns that consumers with wheat or soy allergies or severe sensitivities could face serious or life-threatening reactions if they eat the sauce.

The hazard

Wheat and soy are common allergens, and undeclared ingredients can cause reactions that range from mild symptoms to anaphylaxis. The recall is aimed at preventing exposure for consumers who rely on ingredient labels to avoid these allergens.

What to do

Consumers who have purchased the recalled Honey BBQ Sauce-Mustard should not consume it if they have a wheat or soy allergy or sensitivity. Dispose of the product and request a full refund, using the identifying codes on the label to confirm it matches the recalled batch.

Company contact

Customer Service at 800-955-5080.

Source

Ajinomoto expands recall after possible glass contamination

Ajinomoto Foods North America expanded a nationwide recall of chicken and pork fried rice, ramen, and shu mai products due to possible glass contamination linked to a vegetable ingredient.

- Specific hazard: Possible foreign matter contamination (glass) that could cause mouth injuries or internal harm if consumed.

- Scope/stats: Products with establishment numbers P-18356, P-18356B, or P-47971 produced Oct. 21, 2024, to Feb. 26, 2026, with best-by dates Feb. 28, 2026, through Aug. 19, 2027; sold nationwide and exported to Canada and Mexico.

- Immediate action: Do not eat the affected products; throw them away or return them to the place of purchase.

Ajinomoto Foods North America, Inc. has expanded a recall covering chicken and pork fried rice, ramen, and shu mai products due to possible foreign matter contamination, specifically glass. FSIS said the establishment determined that a vegetable source ingredient, carrots, was the likely source of the contamination.

The hazard

Foreign matter such as glass in prepared foods can cause injuries to the mouth, throat, and digestive tract, and may require medical treatment if swallowed. FSIS categorized the event as Class I (high or medium risk), reflecting the potential severity of harm if contaminated product is consumed.

What to do

Consumers should check their freezers for the affected products and confirm establishment numbers and date ranges. FSIS urges consumers not to consume the recalled items; instead, throw them away or return them to the place of purchase. If you believe you were injured after eating the product, seek medical attention.

Company contact

Consumer Affairs, Ajinomoto Foods North America, at (855) 742-5011 or email customercare@ajinomotofoods.com.

Source

Beef jerky alert for undeclared soy allergen

FSIS issued a public health alert for certain ready-to-eat beef jerky products due to misbranding and a possible undeclared soy lecithin allergen.

- Specific hazard: Products may contain soy lecithin (a known allergen) that is not declared on the label.

- Scope/stats: Punahele Jerky Company products with establishment number EST. 2625 and best-by dates Feb. 17, 2027 or prior; distributed to retail stores in Hawaii and sold online nationwide.

- Immediate action: Do not eat the products if you have a soy allergy; throw them away or return them to the place of purchase.

FSIS issued a public health alert for ready-to-eat beef jerky products from Punahele Jerky Company, Inc., including Dried Hawaiian Style Beef Crisps (Original Salt & Pepper), Uncle K's Beef Crisps, and Kilauea Fire Spicy Beef Crisps. The alert cites misbranding because the products may contain soy lecithin that is not listed on the label.

The hazard

Soy is a major food allergen, and undeclared soy ingredients can cause allergic reactions that may become severe or life-threatening in sensitive individuals. FSIS said there have been no confirmed reports of adverse reactions related to consumption of these products, but the agency issued the alert to warn consumers who may still have the items.

What to do

Consumers should not consume the affected ready-to-eat beef jerky products, particularly anyone with a soy allergy or sensitivity. FSIS recommends throwing the products away or returning them to the place of purchase. If you believe you had an allergic reaction, seek medical attention and report the issue to appropriate authorities.

Company contact

Sabrina Vaughn, Food Safety and QA Compliance Officer, at 808-961-0877; or contact the USDA Meat and Poultry Hotline at 888-674-6854.

Source